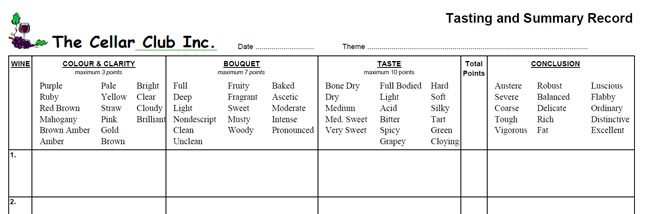

Terms used on our tasting and summary record

Wine

Wines tasted on the night

better study up!

Courtesy of bordeaux.com

Colour & clarity – maximum 3 points

Purple Ruby Red Brown Mahogany Brown Amber Amber Pale Yellow Straw Pink Gold Brown Bright Clear Cloudy Brilliant

The first thing we notice about wine is its colour. At its simplest, wine is red, white or rosé. However, the different nuances of a wine’s colour can suggest lots of things about the wine’s age, its grape variety and even how it was made.

White wines

White wines tend to range in colour from pale lemon to lemon to varying shades of gold. Young wines often have a slight green hue and quite a watery rim. As white wines age the colour deepens, moving through shades of gold to deep amber.

White wines that have been fermented and/or aged in oak will start out more golden in colour than young unoaked wines, which are the palest of all in colour. Some white wines go through a pre-fermentation maceration (cold soak) on the skins – this can add some intensity to the colour. Occasionally Pinot Grigio wines can have a very slight pink hue. This is because Pinot Grigio/Pinot Gris is actually a pinkish/grey-skinned variety. Stronger pressings allow some colour to seep into the juice.

There is a recent return to what is called ‘orange’ wines – whereby white wines are fermented on the skins in a very traditional, more oxidative manner. These wines are orange in colour, partly due to the skins, partly due to the oxidative handling and partly due to their ageing before bottling.

Rosé wines

Young rosé wines range in colour from very pale salmon to sockeye or coppery salmon to varying shades of neon pink. As Rosé wines age, the colour fades to orange or even onion skin colour. The intensity of the rosé colour depends largely on the maceration time whereby the black grapes are gently crushed and the juice is left in contact with the skins for short time to extract just enough colour to achieve the desired ‘pink’ hue.

Red wines

In contrast to white wines, which deepen in colour with age, red wines lose colour and become paler with age. Young red wines start out as varying shades of ruby or crimson. Because red wines are fermented on the skins, and the colour comes from the skins, there is a very wide range of colours. Thick-skinned varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Malbec or Syrah can be almost purple in youth. In contrast thin-skinned varieties such as Pinot Noir, Gamay or Grenache are paler ruby when young.

As red wines age, the rim takes on a garnet hue, then the wine evolves to tawny and finally a brick brown colour. The level of extraction during fermentation also influences the depth of colour in a red wine. More extraction makes for deeper coloured wines.

So the next time you have a glass of wine in hand try to decipher some of these little nuances.

A second facet of a wine’s appearance is its clarity.

Most wine drinkers expect a wine to look clear and bright, not dull or hazy. However, a slight dullness or haze is not necessarily a sign of a major flaw in the wine or even a bad thing. Most wines go through at least one if not more processes post-fermentation to ensure that they are free of any tiny particles visible to the eye. These processes include stabilization, fining and filtration.

A slight haze or dullness in a wine suggests that the wine was minimally handled pre-bottling. Wine is a natural product containing various natural deposits that will precipitate out over time. Therefore, most wines are treated to prevent this happening in the bottle. However, there is a belief that every time you ‘treat’ a wine, you are also stripping out something integral to to the wine itself.

Increasingly wine producers try to minimize or even refrain from these procedures, particularly fining and filtration, in the aim of protecting the integrity of the wine. Everyday wines tend to be more thoroughly treated to ensure crystal clarity, while fine wines are more gently treated or minimally treated.

Bouquet – maximum 7 points

Full Deep Light Nondescript Clean Unclean Fruity Fragrant Sweet Musty Woody Baked Ascetic Moderate Intense Pronounced

Aromas are a very important component of tasting and enjoying wine. Wine aromas are strongly linked to wine flavours and taste, since when we taste a wine we also absorb its aromas through our retro-nasal passage that connects our mouth to our nose.So what exactly do we mean when we talk about aromas in wine? If we like what we smell, we tend to want to drink the wine.Another key reason that aromas are important is to see if the wine is in good condition. Bad aromas can mean a faulty wine – and that is something we certainly do not want.

Wine aromas are very diverse. When we talk about wine aromas we are talking about a number of different things.

While the aromas of any one wine are strongly linked to the particular grape variety/ies that made the wine, they are also influenced by where the grapes were grown (introducing the notion of terroir), by how the wine was made (such as particular winemaking and maturation techniques) and, by bottle age.

Grape or primary fruit aromas

Different grapes have different primary aromas. These vary according to where the grapes are grown. The same grape grown in a cooler climate will have different aromas when grown in a warmer climate. For example, Chardonnay grown in a cool climate like Chablis, will have prominent green apple and citrus aromas. Chardonnay grown in a moderately warm climate such as the Maçon will smell more like melon and grapefruit, while Chardonnay grown in a warm climate will show more pineapple and tropical fruit aromas.

Grape aromas can be fruity and/or floral.

Many white varieties such as Riesling and Viognier have very definite floral notes. Even some reds, such as cool climate Syrah, can have aromas of violets. Fruit aromas most associated with white wines include citrus, orchard, stone and tropical fruit.

Red fruit aromas span the gamut of black and red fruits, all sorts of plums, berries and cherries. Depending on ripeness the aromas can be like freshly picked fruit, jammy, baked or even raisined or dried when ultra ripe.

Mineral, herbal, vegetable and herbaceous aromas

Beyond fruity, wine aromas can be mineral, spicy, vegetable, herbal or herbaceous. While some of these aromas can come from the primary grape, they can also come from the specific terroir, where the grapes were grown.

Herbal aromas can be fresh or dried and include tarragon, mint, eucalyptus as well as the famous Garrigue aroma associated with the wines of Châteauneuf du Papes. Herbaceous aromas include grassy or asparagus notes so often found in Sauvignon Blanc. Mineral aromas can be flinty, stony, earthy or tarry. Vegetable aromas include green or black olive (think cool climate Syrah) as well as all sorts of salad, peas and beans.

Finally, spicy aromas can be inherent to the grape such as black pepper in Syrah, white pepper in Gruner Veltliner or they can come from oak.

Aromas of oak

As well as adding spice, oak can add all sorts of wonderful aromas to a wine including cedar, toast, char, smoke, clove, licorice, baking spices, coconut or vanilla.

Wine making aromas

Cool temperature fermentations tend to preserve and even enhance the primary fruit aromas of the grape, while warmer fermentations tend to produce wines that are more driven by structure than primary fruit. Similarly wines fermented in stainless steel tanks are typically fruitier than those vinified in cask. Techniques such as Malolactic Fermentation (MLF), which converts the harsher malic acid in a wine into a softer lactic acid can add creamy, buttery aromas to a wine.

Aromas of maturity

As a wine ages either in tank, wood or in bottle it undergoes lots of internal chemical reactions. Compounds in the wine breakdown and react with each other to form new compounds and new aromas. Such aromas include leather, cigar box, truffle or mushroom, fusel/petrol, brioche/cereal or honey aromas.

Off-aromas or faults

These are the aromas that we do not want to find in our wine. Sometimes a teeny weeny hint of certain ones is desirable and actually adds complexity to a wine, but it is a thin tightrope and a dominant force of any of them is undeniably a fault. Such aromas include overly oxidative aromas, cork taint (TCA), vinegar, nail polish remover, rotten cabbage, sulphur, stinky barnyard or smelly sweat.

Taste – maximum 10 points

Bone Dry Dry Medium Med. Sweet Very Sweet Full Bodied Light Acid Bitter Spicy Grapey Hard Silky Tart Cloying

Wine flavours are closely connected to wine aromas, because when we taste a wine we also absorb its aromas through our retro-nasal passage that connects our mouth to our nose.

What do we mean when we talk about flavour in wine? Flavour refers to the taste of a wine in your mouth.

As well as reflecting the aromas absorbed retro-nasally, the overall flavour of a wine is also influenced by the wine’s acidity, sweetness, alcohol level, tannins, astringency, body and in sparkling wines by its fizziness, as these components can accentuate or neutralize the flavours.

Flavour origins

All grapes contain flavour compounds, some more than others. Grapes also contain flavourless compounds, which are activated through different chemical reactions that occur during winemaking and wine maturation, thereby releasing additional flavours into the wine. This is why the flavour of a wine is more complex than the flavour of grape juice, and also helps explain why the flavours of a mature wine are more complex than those of a young wine.

Flavour intensity

As with aromas, wine flavours can be categorized as fruity, floral, spicy, mineral, vegetal or oaky. Fruit flavours can be fresh and lively or jammy, baked or even raisined. Apart from identifying types of flavours we also consider the intensity of these flavours. More intense, concentrated flavours are typically a sign of a better wine, due perhaps to riper grapes, smaller-berries, a stricter selection of only the best grapes or longer maceration and/or extraction time during vinification.

Flavour definition

Flavours also contribute to an overall taste sensation. Wine flavours can be bold and forward or subtle and restrained. They can be quite precise and focused or somewhat muddled and vague. They can be generous or lean, tight-knit or loose-knit. In short, they flavours be well defined or poorly defined.

Flavour maturity

As with aromas, wine flavours change as a wine matures. In a young wine, the youthful primary fruit flavours prevail. With age, these are replaced by more developed flavours of leather, earth, spice, truffle and game in red wines, or honey, nutty, fusel and toasty brioche flavours in whites.

Effect of acidity, alcohol, tannin and fizz on flavour

Acidity brightens a wine’s flavours and makes them stand out. Alcohol creates a feeling of warmth. When in balance it adds to the overall taste sensation. When high, it can give a perception of sweetness to a wine, and when too high it gives a burning sensation, and cut short wine flavour.

Depending on the amount, ripeness and texture, tannin can add unctuousness and plump out a wine’s flavours, or it can make a wine taste astringent and bitter. The flavours of young very tannic wines, particularly top Bordeaux or Barolo wines can be hard to appreciate until the tannins start to resolve and integrate.

Finally, bubbles accentuate flavours in a wine. Tiny persistent bubbles enhance flavour and add elegance, whilst, larger coarser bubbles mask flavour with froth.

Conclusion

Austere Severe Coarse Tough Vigorous Robust Balanced Delicate Rich Fat Luscious Flabby Ordinary Distinctive Excellent

Length and finish are words often used by wine tasters.

What do they mean? And what words might you use to describe them?

Length is a tasting term to describe how long the taste of a wine persists or lingers on your palate after you have swallowed (or spit, if tasting professionally) the wine.

Length is essentially, as it implies, a measure. A wine’s length may be described as long, moderate or short.

In general, a long length is considered a sign of high quality.

A wine’s length differs from its finish (although the terms are often used interchangeably), in that, in my opinion, the finish is a more of a descriptive term. It describes the very last flavour or textural sensation left in your mouth after swallowing or spitting the wine.

Terms used to describe the finish of a wine include spicy, minerality, savoury, sweet, bitter, hot, harsh, rich and so forth – essentially the same adjectives that you might use to describe flavour or texture of a wine.

Related pages

Central Otago: The New Zealand wine region with vineyards to rival Burgundy

Susy Atkins, Daily Telegraph UK | July 2024 The world’sRead more…